Un Mythe Immaculé

Overlooking our family’s wooded property in Central Vermont, my historian father-in-law made a comment that sparked the idea behind this series. He spoke about how the dense and established forest surrounding us had actually been clear cut for lumber at the turn of the 20th Century. I was immediately struck by how thick, encompassing and rich this woodland currently is. I struggled to process, that only 100 years ago, this forest was a low cut field full of stumps. This picture was in stark contrast to my internal narrative of the American Wilderness.

He went further. “Almost the entire state had been cleared at one point for lumber”.

I am a midwestern city dweller for the majority of the year. I live in a densely populated area where trees live on tree lawns and neighbors are always easily accessible if not too close for comfort. I spend a few weeks of the year on our 4 acres of Pine forest in Vermont. Maybe the brevity has added to the rustic fantasy, however Vermont exists in my mind as synonymous with expansive nature and the untouched landscape. The idea that our small plot of forest (and my idealized portrait of the green mountain state) looked drastically different 100 years ago, was hard for me to imagine. Turns out, I’m not the only one.

There is a tendency to believe the natural landscape is eternal. We imagine that as long as we can preserve what is left, it will remain as it has always been; was meant to be. We see our viewpoint as one unaltered from that of one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand years ago. We assume the ebbs and flow of nature are steady and ever so slow in comparison to the pace of societal and human intervention.

This realization that each landscape has a history, a shifting and evolving foundation, is the basis for this body of work. This shake-up within my own understanding and perspective, became an opportunity for inspiration and discovery. In losing the pristine myth of my beloved landscape, I began to scratch the surface of really engaging with it. The very ground I stood on became not only layers of pine needles, dirt and stone but a rich tapestry of evolving and living history; losing none of its (previously romanticized) beauty despite having in fact been repeatedly and impactfully altered by the human hand. With my father-in-law’s passing comments in mind, I embarked on a path of research, and in effect a reintroduction to my own understanding of the American wilderness.

In an effort to gain a deeper understanding of the history of New England’s forests, I found William M. Denevan’s paper, The Pristine Myth: The landscape of the Americas in 1492 (1992), and then subsequently Charles Mann’s book 1491. It quickly became evident that clear cutting and reforestation of the past hundred years, were only the tiniest tip of a large and expansive iceberg. In the research before me, I was introduced to the far more complicated history of our American wilderness and moreover the historical misrepresentation of those peoples who populated, farmed, hunted and undeniably, repeatedly and dramatically altered them for thousands of years before the first European settler set foot on American soil.

Popular and widespread mythology surrounding the pristine American Wilderness, at the time of early European colonization and the centuries to follow, paints a vivid picture of the untouched and bountiful American landscape, densely populated with both flora and fauna. Well intentioned conservationists of the previous century have used this image as the ideal we strive for, the perfectly balanced and natural harmony of our forests prior to European settlers who saw nature as something to be conquered. This fairytale, or “pristine myth”, is not without its cast of human characters. However, the native people of this story and landscape have been flattened and simplified to fit the narrative of our myth. Within this story, Native Americans are in complete harmony with nature; the streams are overflowing with fish and the forests with game. There is no need to conquer, alter or manipulate a landscape as these people know that nature will always provide.

This is of course a vast simplification at best. Native Americans have been altering the landscape for a milenia through anthropogenic forests via cultivation. Native Americans also managed forests through intentional fires for generations, centuries prior to the aforementioned clear cutting of the previous century. Entire societies of people have populated this landscape; countless incarnations of these forests have emerged as generations of rich and varied narratives have transpired. And while the myth perpetuated by 19th-20th century conservation efforts was an attempt to heal the land in response to the unbridled and potentially devastating impact of clear cutting, decimation of entire species and the widespread and highly visible impact of our industrial period- there is the simultaneous, assumably inadvertent, disservice to the entire history of thousands of indigenous cultures who inhabited these very same lands conservationists sought to protect.

As we pull ourselves out of the simplified notion of the unaltered wilderness, pristine and perfect, prior to European intervention; we must accept that we are but a small part of an ever changing environment. The human impact on history becomes less centralized and our role in preservation becomes hazier as our target begins to shift. What point in time, what incarnation are we aspiring to? Certainly there is no denying of he ever increasing severity of human impact on our environment. However, when we see ourselves as part of the environment from the beginning, an integral and historically impactful piece of the most complex web- we are left with far more questions than answers. This ambiguity can be incredibly unsettling. Such is the infinite; such is nature. In a world exponentially approaching dire, irreversible and detrimental change, we must strive to be aware and introspective of our history and impact.

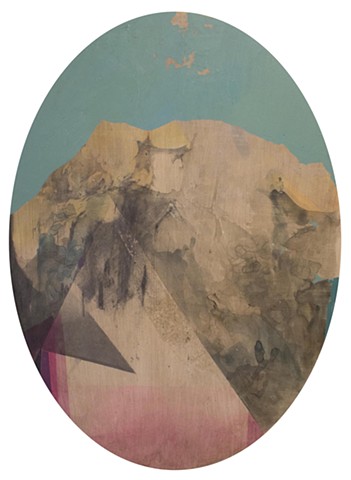

In these paintings, I strive to understand and balance these truths, through historical and imagine narratives. While making no attempt to illustrate a linear history, the paintings are a juxtaposition of the real and imagined human impact on our natural world. They aspire to evoke a conversation.